Power on Tap

How to increase the transmission capacity of the electric power grid efficiently and economically - by Samuel Renggli

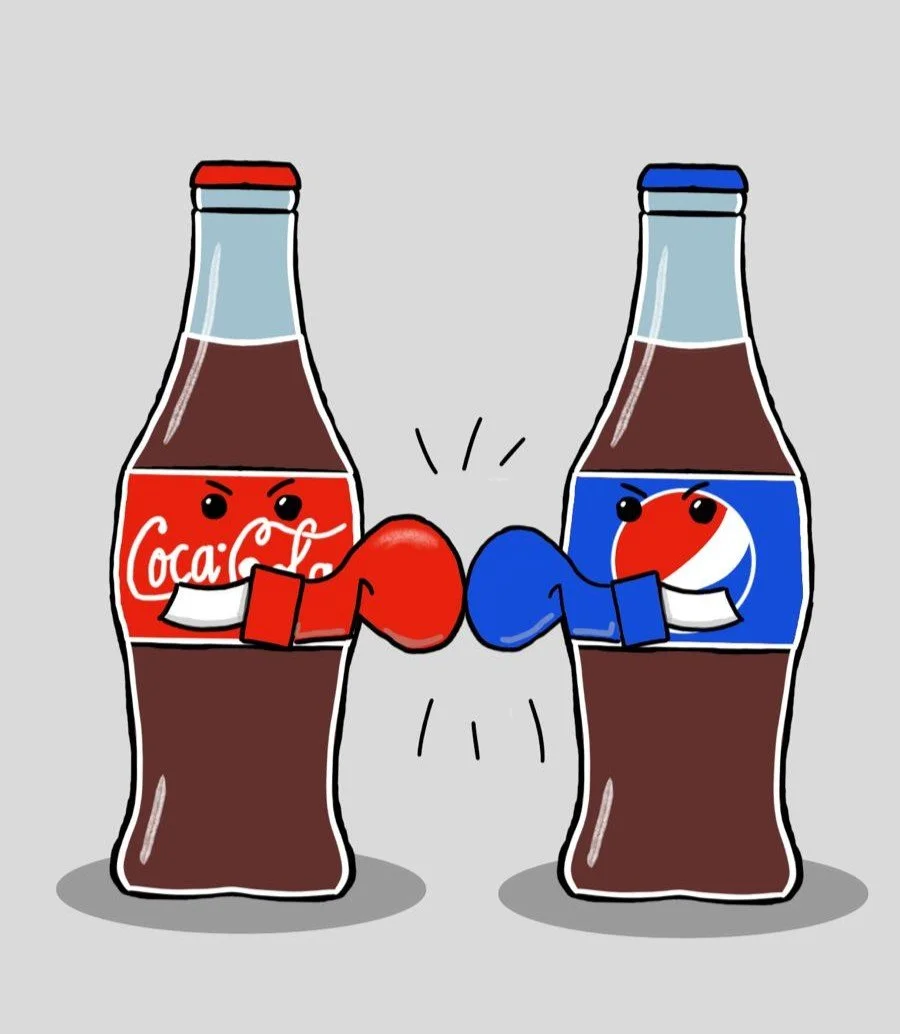

When you order a beer at a bar, you actually mean the liquid of the drink and not the foam that also ends up in the glass. However, if there is no foam at all, it means that the beer is poorly carbonated and undrinkable. In short, the right amount of foam is required, and it must be transported with the liquid through a pipe to the tap.

In that regard, the electric power grid is like the pipe to the beer tap. Active power, the “liquid”, and the right amount of reactive power, the “foam”, must be transported through transmission lines to consumers.

Similarly, when we talk about consuming electricity, we actually mean active power. With rising electricity demand, transmission capacities to supply active power must be increased. The simple solution of adding more power lines to the grid is costly and takes a long time.

So, are there efficient and economical alternatives to boost the current infrastructure to supply more active power while guaranteeing that we have the necessary reactive power?

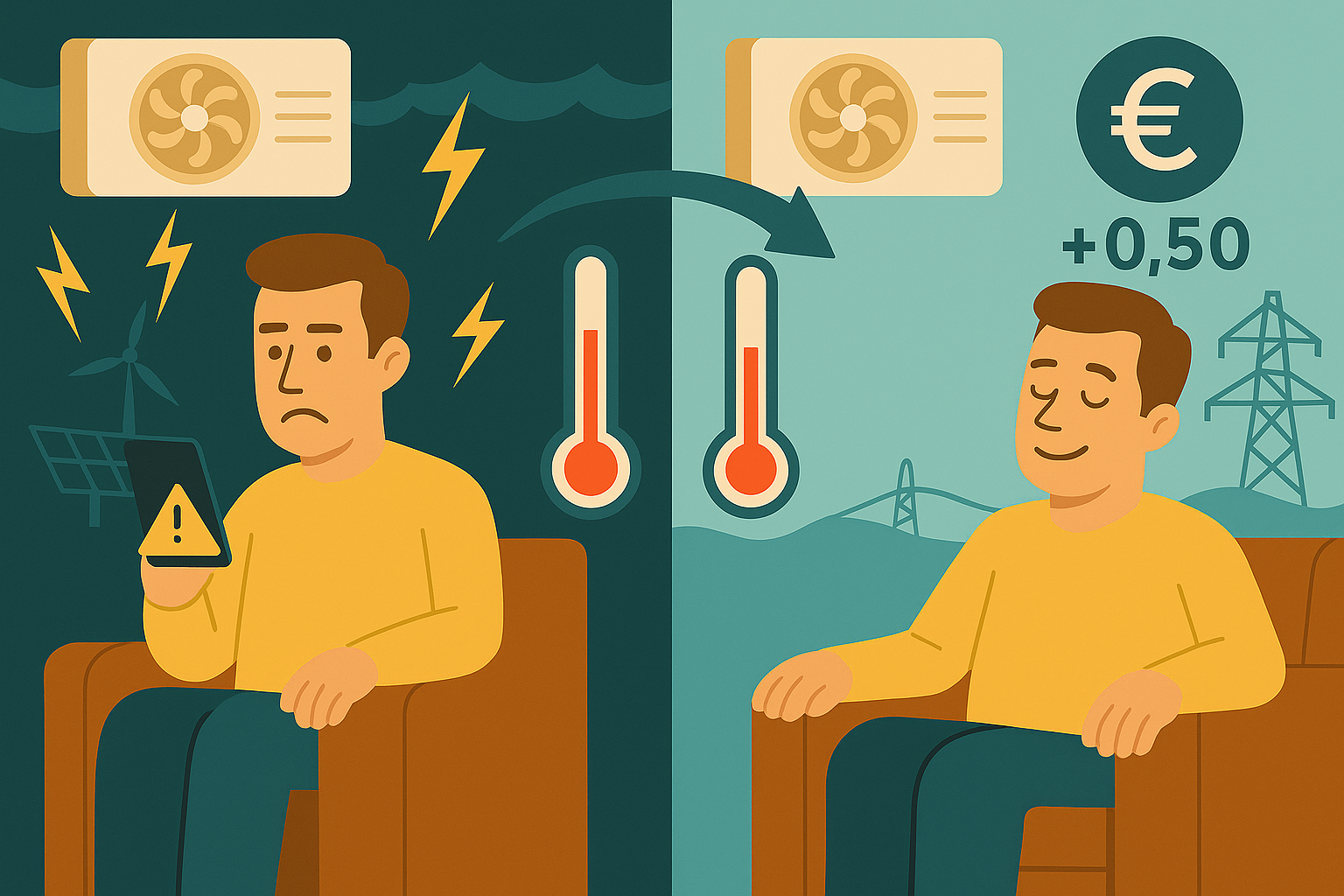

The solution approach is based on so-called “inverters” installed with photovoltaic systems on residential roofs. These devices primarily feed the active power generated by solar panels into the grid. However, they can also inject or absorb small amounts of reactive power even when the sun is not shining. In comparison to the pipe and the beer tap, this means that the amount of foam is precisely controlled right at the tap. Therefore, no more foam must flow through the pipe, and the freed-up capacity allows more liquid to flow.

The same effect occurs in the power grid, where the transmission capacity for active power increases because no reactive power has to be transported. The use of already installed inverters makes this solution a viable alternative to expensive grid-upgrades.

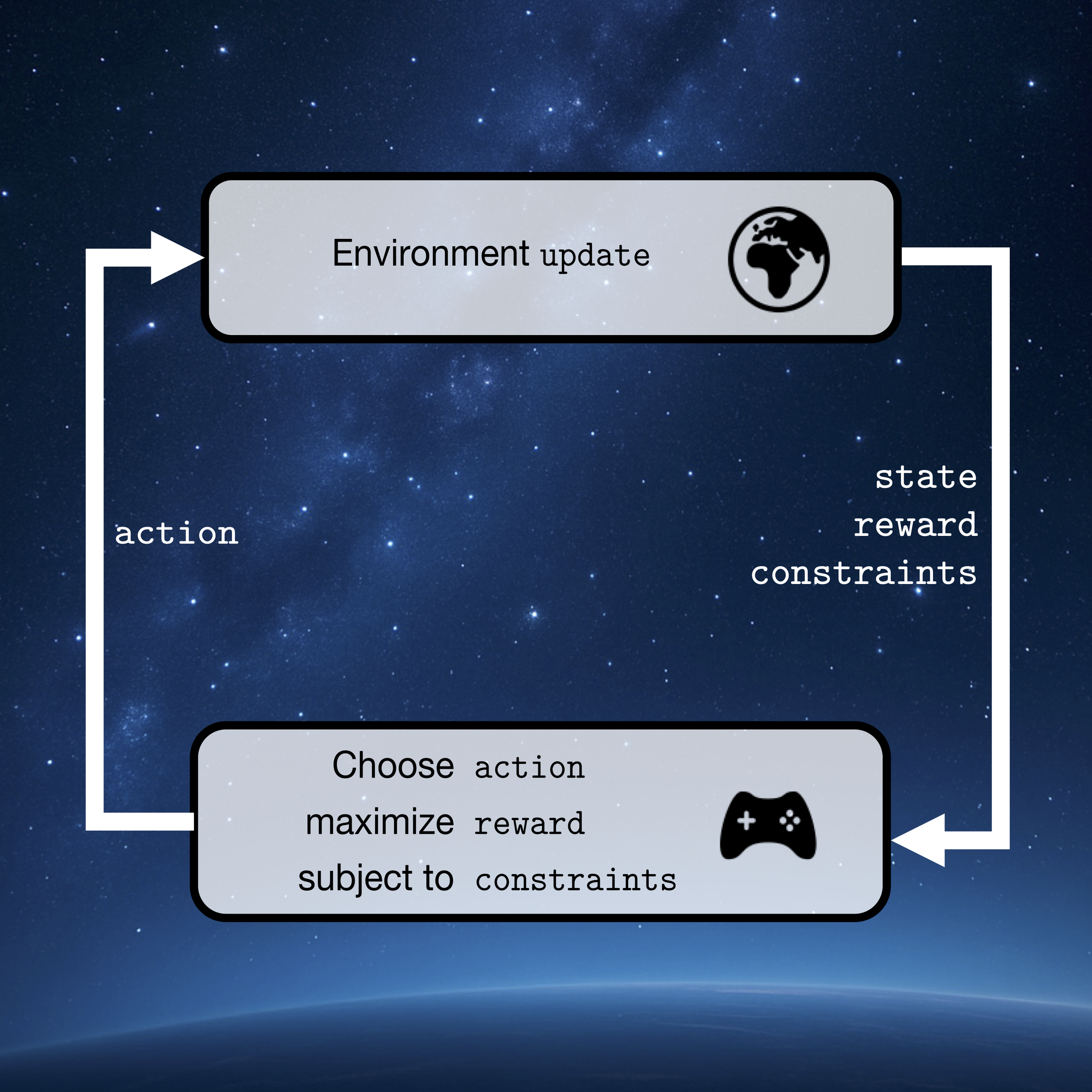

Unlike a single pipe, the electric power grid is vastly more complex due to the enormous number of lines and connected devices. Consequently, individual inverters interact with one another and must be coordinated. This challenge becomes intractable for the entire large power grid. Therefore, we apply new methods to subdivide the grid. The large problem is simplified into manageable subproblems. We then solve these subproblems mathematically to determine the operational settings of the inverters.

In this way, every house with a photovoltaic system knows how much “foam” to produce, and we can avoid building additional power lines.

Text by Samuel Renggli; illustration created with Microsoft CopilotCan batteries support Run-of-River power plants during periods of low electricity prices? - by Yannick Schüpbach

Using real-time sensors to detect early warning signs of power grid instability - by Ioannis Papadopoulos

How to increase the transmission capacity of the electric power grid efficiently and economically - by Samuel Renggli